The Gender Pay Gap Among Economics Majors: Geographical Variation

Published:

The Gender Pay Gap Among Economics Majors: Geographical Variation

The gender pay gap is a well-documented phenomenon across nearly all industries and academic disciplines. But what about among economics majors—students who study markets, incentives, and labor dynamics? Surprisingly, even in this group, a significant pay gap exists, raising important questions about its causes, implications, and geographical variations.

The Evidence: Economics Graduates and Earnings

Research consistently shows that men who major in economics tend to earn more than their female counterparts, both immediately after graduation and later in their careers. Studies tracking earnings indicate that male economics graduates often earn 10-20% more than female graduates, even when controlling for occupation, work experience, and hours worked.

Geographical Differences

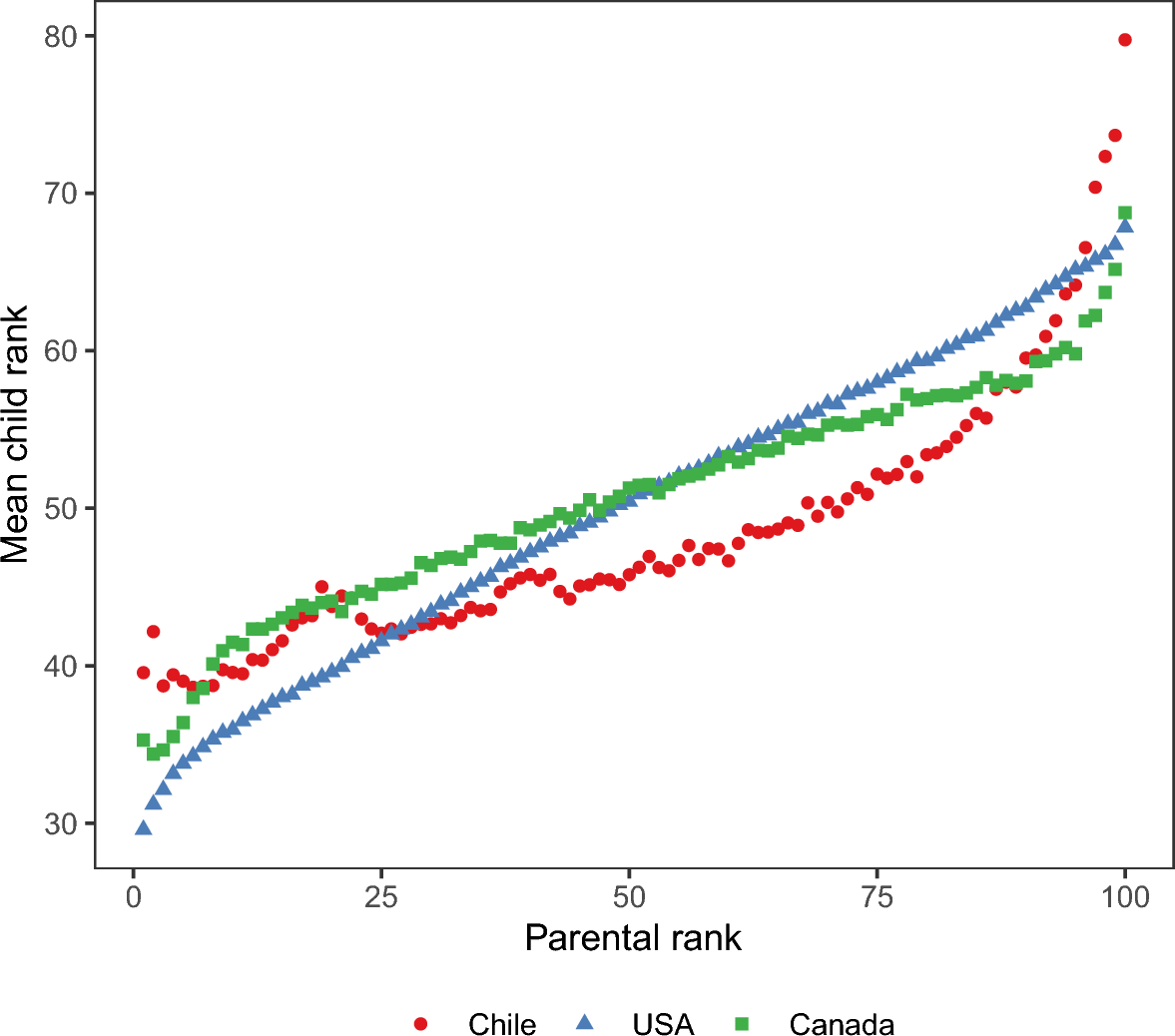

The gender pay gap among economics majors varies significantly across countries and regions:

- United States & United Kingdom – Studies show that male economics graduates earn about 15-20% more than their female counterparts, even after adjusting for job type and experience.

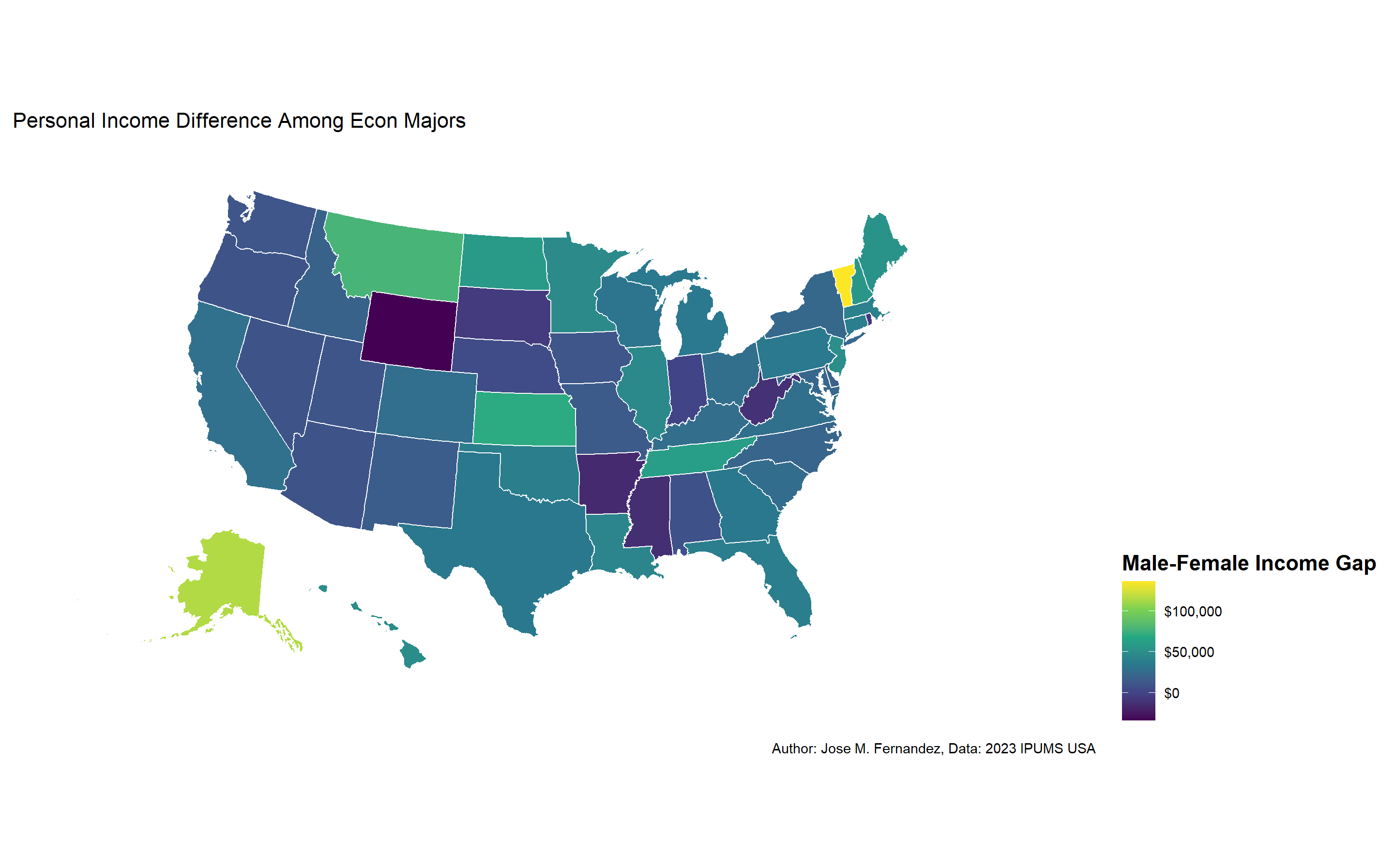

We will use data from IPUMS to look a differences in median personal income among Econ Majors by sex and state of residence.

- I personally like using the Urban Insitutest mapping package

urbnmapr. You really do not need to know GIS to create maps that highlight different statistics by Region, Country, State, or County.

- You will need a couple of packages to make these graphs. So before we start, please run the following code to install the packages.

devtools::install_github("UrbanInstitute/urbnmapr")

install.packages("remotes")

remotes::install_github("UrbanInstitute/urbnthemes")

Next, you will need some data. I obtained the following data from IPUMS 2023 USA online analyzer. You can download my file for this post. Get Data Here

Next, you will need to run the following R code

library(urbnmapr)

library(tidyverse)

# Get state data

library(readr)

dif_sal <- read_csv("C:/Users/jmfern02/Downloads/means (3).csv")

dif_sal <- dif_sal %>% left_join(states, by="state_name")

library(ggthemes)

State4<-dif_sal %>%

ggplot(mapping = aes(long, lat, group = group, fill = `Male-Female`)) +

geom_polygon(color = "#ffffff", size = 0.25) +

coord_map(projection = "albers", lat0 = 39, lat1 = 45) +

scale_fill_viridis_c(labels = scales::dollar_format()) +

theme_map() +

theme(legend.position = "right",

legend.direction = "vertical",

legend.title = element_text(face = "bold", size = 11),

legend.key.height = unit(.2, "in"),

axis.title.x=element_blank(),

axis.text.x=element_blank(),

axis.ticks.x=element_blank(),

axis.title.y=element_blank(),

axis.text.y=element_blank(),

axis.ticks.y=element_blank()) +

labs(fill = "Male-Female Income Gap", title = "Personal Income Difference Among Econ Majors", caption = "Author: Jose M. Fernandez, Data: 2023 IPUMS USA")

State4

We observe the largest differences in Alaska and Vermont where the gap is over $100,000. However, there are a few states where women hold an advantage: Wyoming, Arkansas, Mississippi, West Virginia, Rhode Island, and South Dakota. The smallest observed difference in Indiana. The average premium for men is $29,577.

Possible Explanations

Several factors contribute to this persistent wage gap:

1. Occupational Choices

Male and female economics graduates tend to enter different fields. Men are more likely to pursue careers in finance, consulting, and tech—sectors known for high salaries—while women are more likely to work in government, nonprofit organizations, or education, where wages are generally lower.

2. Negotiation and Career Progression

Research suggests that women, on average, are less likely to negotiate salaries aggressively, leading to lower starting wages and slower salary growth over time. This pattern is particularly evident in Anglo-American countries, where individual salary negotiations are common.

3. Workplace Discrimination and Bias

Even when controlling for occupation and experience, gender-based pay disparities persist. Implicit biases in hiring, promotions, and salary negotiations may disadvantage women, particularly in male-dominated industries like finance and tech.

4. Differences in Specialization

Within economics itself, men and women may focus on different subfields. Women are more likely to study labor and public economics, while men are overrepresented in finance and macroeconomics, which may lead to differing career trajectories.

5. Work-Life Balance Considerations

Women often face greater societal expectations regarding work-life balance, particularly in countries with limited parental leave policies. These pressures can influence career choices, hours worked, and long-term earnings potential.

Addressing the Gap: What Can Be Done?

Understanding the sources of the gender pay gap is the first step toward narrowing it. Some possible solutions include:

- Encouraging More Women in High-Paying Sectors – Mentorship programs and targeted career support can help more female economics majors enter finance, tech, and consulting roles.

- Salary Negotiation Training – Teaching students negotiation skills early in their careers could help reduce disparities in starting salaries.

- Addressing Bias in Hiring and Promotions – Employers should actively work to eliminate gender bias in pay and promotion decisions.

- Flexible Work Policies – Policies that support work-life balance, such as parental leave and remote work options, could help reduce gendered career trade-offs.

Conclusion

The gender pay gap among economics majors highlights broader issues of gender inequality in the workforce. While individual choices play a role, structural and cultural factors also contribute to wage disparities. Addressing these challenges requires a combination of policy changes, employer initiatives, and individual empowerment.